VITA

A Visiting Researcher at the University of Ottawa, she is a scholar and a prominent women's rights activist from Afghanistan. She started her academic journey in 2012, when she became an Assistant Professor at the Kabul University. Since then, she has lectured courses on public policy with the focus on human rights, gender equality, and women empowerment. She served in several local research institutions and think tanks from 2015 to 2019 on issues related to women's rights and gender-based policy reforms. From 2019 to 2021, Shabnam was Commissioner and Head of the Women’s rights Promotion and Protection Unit (WPU) in the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC). Under her leadership, the WPU designed and implemented interventions that contributed to the protection and promotion of women's rights in Afghanistan. Prior to the Taliban regime, Shabnam Salehi advocated for women's participation in private and public institutions, and helped strengthen women's participation in the decision-making. She also contributed to reform laws affecting marriage, virginity tests, divorce, transgender rights, sexual harassment, violence against women, and female prisoners. Since August 2021, Shabnam Salehi continuous her advocacy work for women's rights in Afghanistan in exile.

AFGHANISTAN

Shabnam Salehi

A Visiting Researcher at the University of Ottawa, she is a scholar and a prominent women's rights activist from Afghanistan. She started her academic journey in 2012, when she became an Assistant Professor at the Kabul University. Since then, she has lectured courses on public policy with the focus on human rights, gender equality, and women empowerment. She served in several local research institutions and thinks tanks from 2015 to 2019 on issues related to women's rights and gender-based policy reforms. From 2019 to 2021, Shabnam was Commissioner and Head of the Women’s rights Promotion and Protection Unit (WPU) in the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC). Under her leadership, the WPU designed and implemented interventions that contributed to the protection and promotion of women's rights in Afghanistan. Prior to the Taliban regime, Shabnam Salehi advocated for women's participation in private and public institutions, and helped strengthen women's participation in the decision-making. She also contributed to reform laws affecting marriage, virginity tests, divorce, transgender rights, sexual harassment, violence against women, and female prisoners. Since August 2021, Shabnam Salehi continuous her advocacy work for women's rights in Afghanistan in exile.

Thank you for conducting this interview with us. How are you today?

I am fine, and like every other day for the last months, I started the day by reading the news and responding to the messages and emails about the human rights violations in Afghanistan, and communicating with the human rights activists, with the goal of advocacy for women's rights.

How did you become a human rights lawyer and chose this profession?

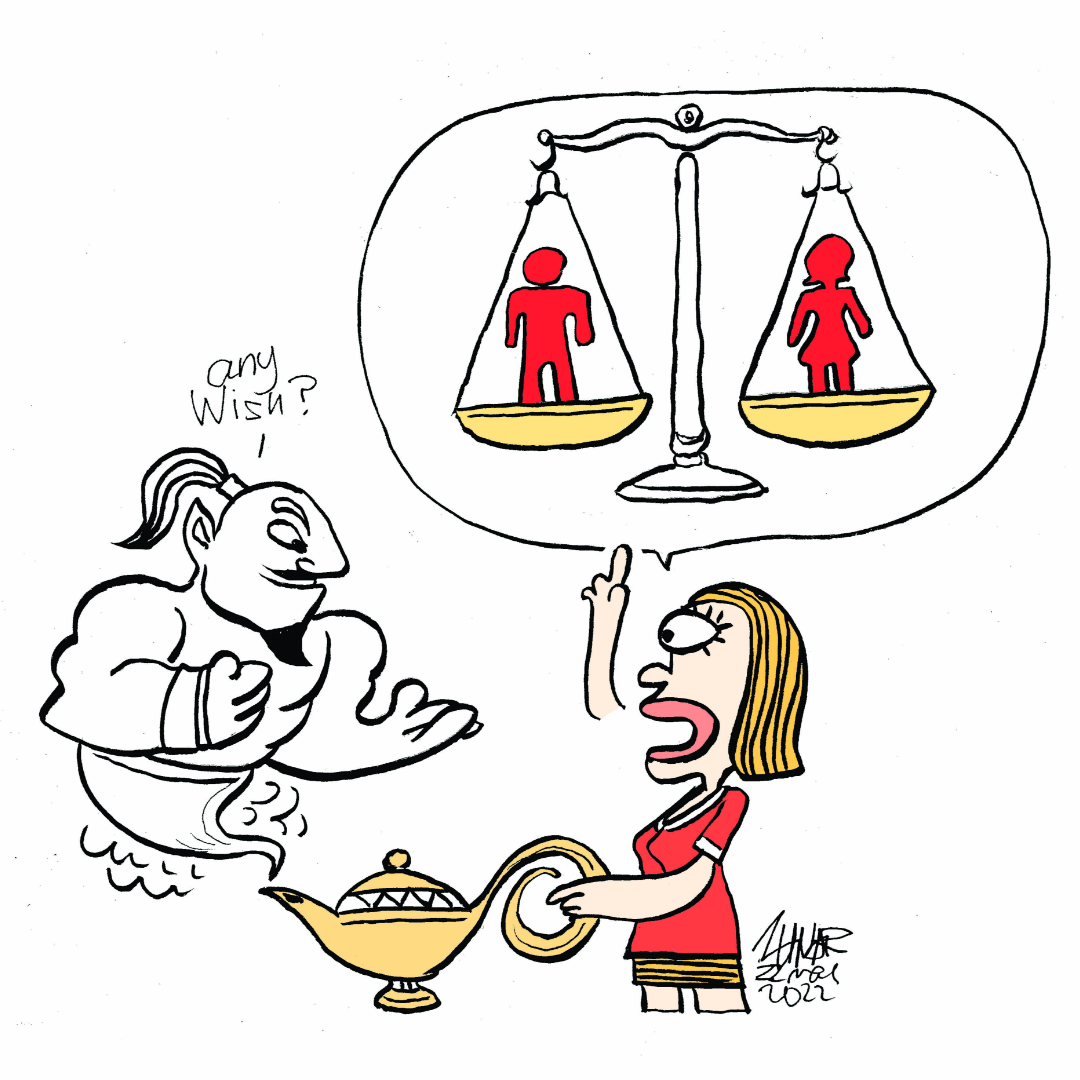

I was born in a highly marginalized community in Afghanistan, in which there was systematic discrimination against women. There were no schools for girls in my village and no females with even the lowest literacy. I was fortunate that my parents supported my education and resided in places, where I could access education. While I was in secondary school, I devoted my full attention to getting insights on discrimination against women. I framed it as a problem, understood its severity, and decided to work towards finding solutions. I envisioned a future where all men and women could have equal rights and opportunities. Before the collapse of the government in 2021, I was serving as a Commissioner at the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC), as head of the Women Rights Protection and Promotion Unit (WPU). I closely worked with the victims, government entities, civil society, and the international community. I had always one goal to achieve, and that was to contribute to the assurance of justice in the country, especially to ensure equal rights for women.

As a Commissioner at the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, what were your main responsibilities?

I helped reform laws on marriage, virginity tests, divorce, transgender rights, and sexual harassment. I advocated for women's meaningful participation in the Afghan society. As head of the Women Rights Protection and Promotion Unit (WPU), I strategized the objectives and strengthened their potential for implementation. The WPU, under my leadership, designed and implemented interventions that enhanced coordination and communication between the stakeholders. I particularly worked on the cases of sexual harassment and violence against women. It was likewise crucial to enable Afghan women so that they could participate in the Afghan peace process. Every year, my team registered and processed around 5,000 cases of domestic violence and would help the victims to access justice institutions.

How do you assess the situation of Afghan female lawyers before the Taliban in comparison to the environment after August 2021?

Before the Taliban, we had a legal and policy framework for protecting and promoting women human rights lawyers. There was a solid political will among the diverse decision-makers for supporting women lawyers. However, there were constant security threats. In 2020, two of my colleagues were killed, and we received several intimidations. Every day, I received messages from the human rights defenders about the threats they were receiving both from warlords and the Taliban. Nevertheless, those under the severe threats would eventually find a space and manage their human rights activism. Now, it is a much different context. There is neither laws for the protection and promotion of human rights, nor exclusive attorney or courts to prosecute cases of violence against women. Politically speaking, the de facto regime lacks the commitment to the women's rights. Today, human rights defenders are suppressed; they are hiding because of their activism. Some are already threatened, imprisoned, tortured, and even murdered. As a matter of fact, there is no safe space for them to live in Afghanistan.

Have you conducted any investigations that led to attacks and threats against you?

Yes, I led a number of investigations on human rights violations by the former government officials and the Taliban, and advocated for the reform of discriminative laws and policies. I investigated high-level political and sexual harassment cases and presented the report to the president of Afghanistan. I also conducted investigation of the cases of sexual harassment of female football players, which attracted a lot media attention. Two weeks before the collapse of the government, I started an inquiry into the systematic killings in Speen Boldak in Kandahar, committed by the Taliban. These activities were highly sensitive and full of risks, posing threats to my family and me.

“Today, human rights defenders are suppressed; they are hiding because of their activism.”

Since the Taliban came to power, many female human rights lawyers have left the country, arrested or banned from their activities. What did you do?

Throughout my work at Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, I advocated for the punishment of the criminals convicted of women's rights violations. Some of them were members of the Taliban, and other influential people with strong political, economic, and social power. After the Taliban returned, as they were released from prison, they called many times and threatened my family and me, and were looking for us. We hid until the evacuation and turned off our cell phones and communication pipelines. My family and I got assistance for evacuation and left the country, while watching the destruction of my years-long efforts and hopes. I left everything behind; my career, the basis I made for change, and years-long work achievements. It was a total disaster for me. Even now after months, I am not able to overcome the trauma and stress.

Could the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission continue to function, as many members like yourself already escaped the persecution?

The leadership of the AIHRC was evacuated, and we are trying to relocate the remaining staff and colleagues. The AIHRC’s activities is suspended in Afghanistan. The Taliban occupies our office, and they are not allowing anyone to enter the building. In a volunteer capacity, my colleagues and I advocate for women's rights. If the current political trend of suppression continues, human rights defenders will be continuously persecuted, and forced to leave the country.

Do have any advice for the Afghan female human rights lawyers, especially those who are in exile?

We still have an obligation and responsibility to protect and promote human rights. We need to build on our work, despite the abundance, many challenges and obstacles.

Afghanistan