CAMBODIA

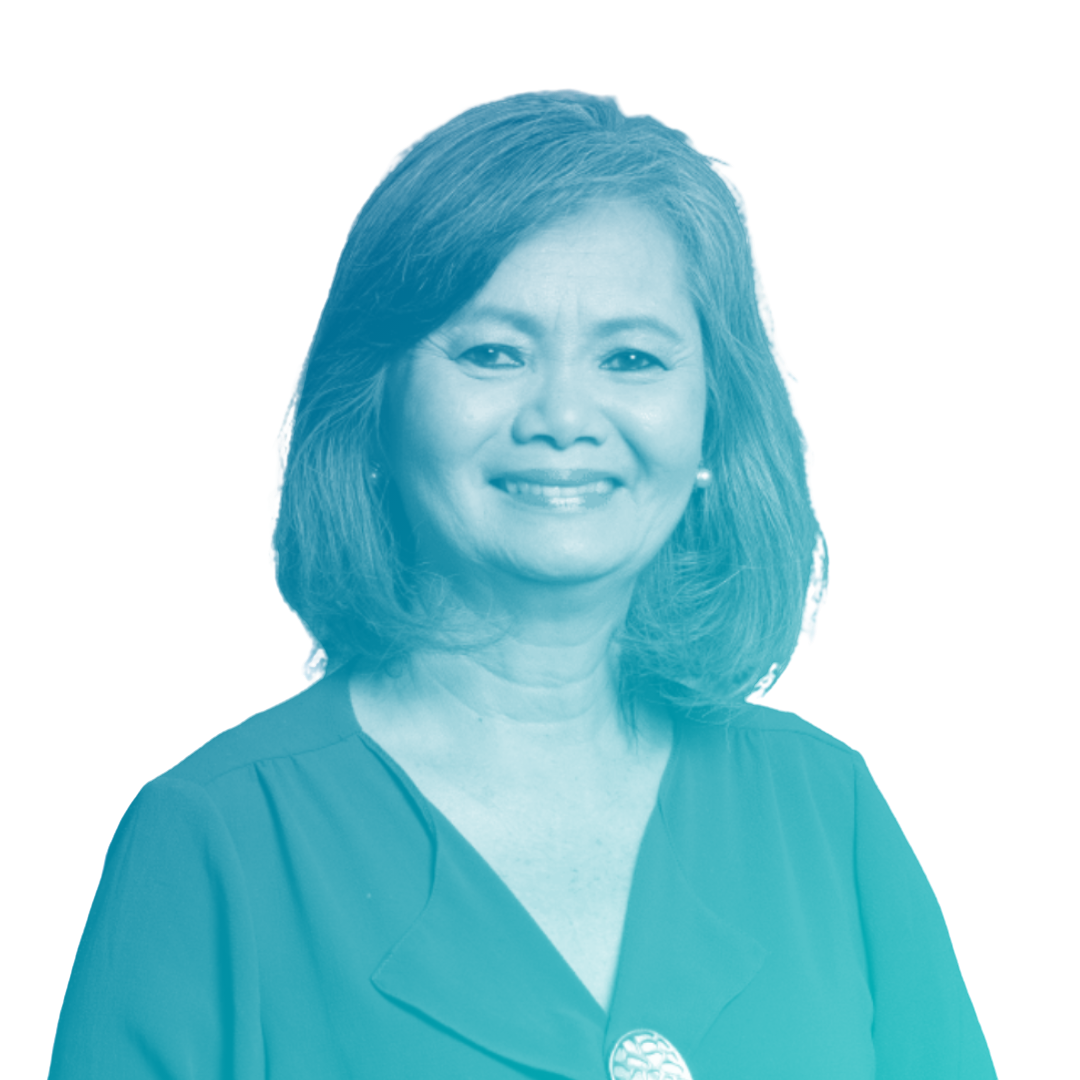

Mu Sochua

Mu Sochua is a Cambodian politician who has dedicated her life to fighting for women’s rights and democracy in Southeast Asia. She spent most of her adult life in exile in the United States. When she returned to Cambodia in 1991, she strove to rebuild her country, first by founding Khemara, an NGO for women’s empowerment, and by joining the FUNCINPEC party. She eventually won a seat in parliament. She served as the first Minister of Women and Veterans’ Affairs between 1998 and 2004. As the government grew increasingly corrupt under Prime Minister Hun Sen, Mu Sochua stepped down and became Vice President of the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), Cambodia’s main electoral opposition party. She dedicated her work in combating sex trafficking and promoting gender equality. Mu Sochua received a Vital Voices’ Leadership Award, and was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in 2005. She is once again living in exile after Mr. Hun Sen dissolved the CNRP and threatened its leaders in 2017. Fighting to ensure the restoration of democracy and freedom in Cambodia, she travels the world and meets with international leaders to call for action against Mr. Hun Sen’s government.

VITA

Mu Sochua is a Cambodian politician who has dedicated her life to fighting for women’s rights and democracy in Southeast Asia. She spent most of her adult life in exile in the United States. When she returned to Cambodia in 1991, she strove to rebuild her country, first by founding Khemara, an NGO for women’s empowerment, and by joining the FUNCINPEC party. She eventually won a seat in parliament. She served as the first Minister of Women and Veterans’ Affairs between 1998 and 2004. As the government grew increasingly corrupt under Prime Minister Hun Sen, Mu Sochua stepped down and became Vice President of the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), Cambodia’s main electoral opposition party. She dedicated her work in combating sex trafficking and promoting gender equality. Mu Sochua received a Vital Voices’ Leadership Award, and was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in 2005. She is once again living in exile after Mr. Hun Sen dissolved the CNRP and threatened its leaders in 2017. Fighting to ensure the restoration of democracy and freedom in Cambodia, she travels the world and meets with international leaders to call for action against Mr. Hun Sen’s government.

Last year you told us that a Cambodian court in a so-called trial in absentia sentenced you for 20 years in prison. How is your case going before the court?

I would not call it a trial. It is called a trial, if the defendant has the opportunity, the right and the liberty to defend herself. I would say persecution, political persecution. Thus, it is not a trial in that sense. I defend myself with my voice, not within the court, but outside the court.

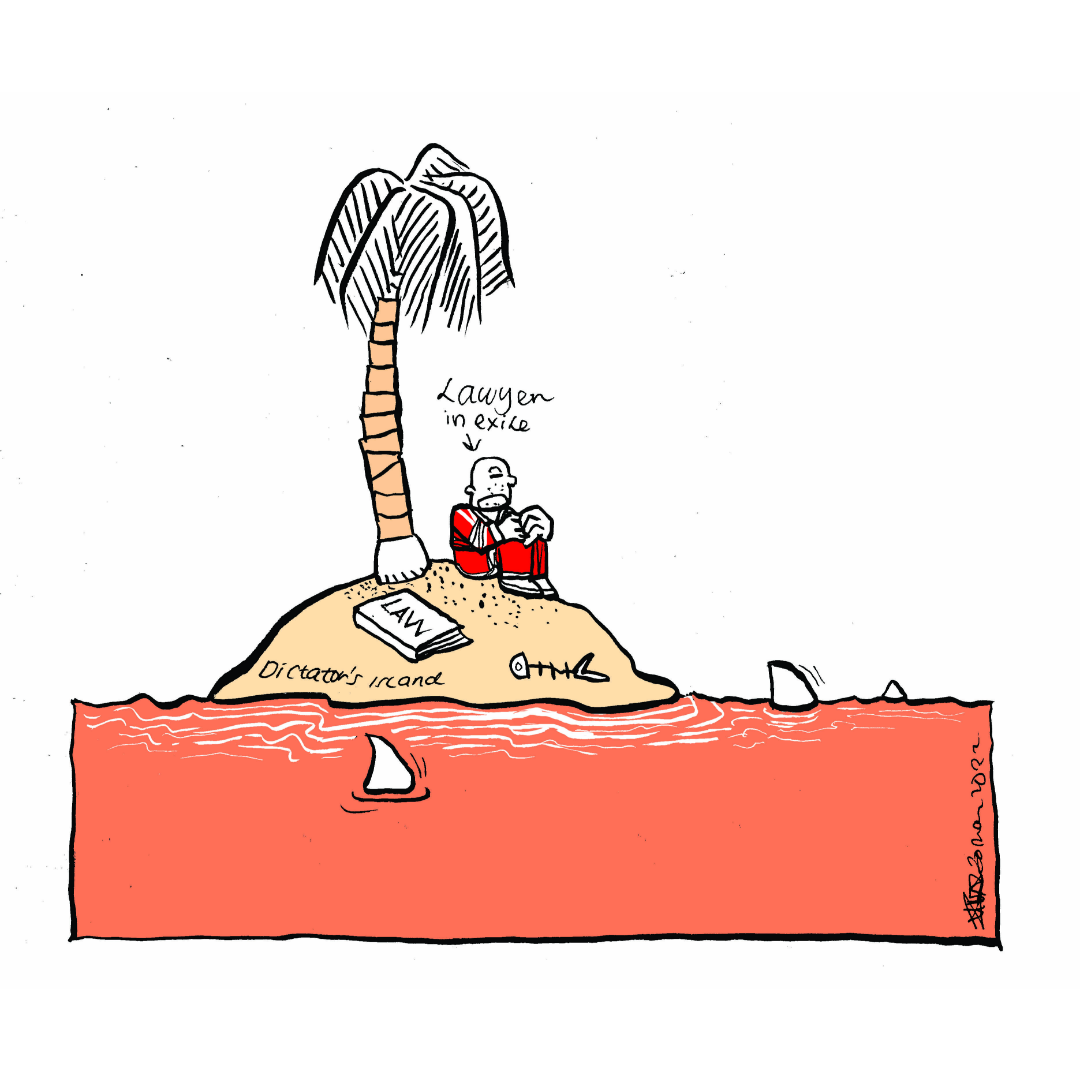

As the court proceedings were conducted in absentia, have you received any legal aid from a lawyer or any support from lawyers’ community?

I have a choice, because I am a dual citizen of the United States and Cambodia. I do consider both ways. I have a Cambodian lawyer and I communicate with him via the App ‘Signal’. He represents me before the court. He gives me advice on what to do and I provide him clear instructions on how to represent me. My main point is to get the right to go back to Cambodia and defend myself. Moreover, I demand fair trial as a Cambodian citizen. I also have a pro bono lawyer in the United States. I have taken my case to the Senators in Rhode Island and they have intervened on my behalf and written to the US Embassy in Cambodia to help, so that I can return to Cambodia as a US citizen.

Have your lawyer in Cambodia experienced any challenges or obstacles in presenting you before the court or providing you with any legal support?

My lawyer’s name is Som Sakhun, and he is one of the pro bono lawyers for political cases. Because of the link to political cases, he is not treated as good as the lawyers of the government or private lawyers who pay under the table and can use the influence of the government on the court. Even the clerks, he tells me that he has to wait sometimes days to get any records from the clerks, because he cannot pay the clerk, it is a political case, and they are hesitant to provide information; and administratively speaking, this is a first challenge. The second challenge is that when he defends my case, he knows that he is given the answer not by the book, but by the power of the regime.

“It is respecting fundamental rights of the defendant, human rights, human dignity and justice.”

This brings us to the important issue, which is the situation of human rights lawyers. How indeed is the situation of human rights lawyers in Cambodia?

They are very frustrated. First, they are put in a different category, because they defend human rights and political cases. They have the hardest time to get access to the records and often face warnings. I had a lawyer for another case in 2009, and when I filed a case to the court against the Prime Minister for political discrimination, at that time, my lawyer was forced to give up the case or he would have lost his position and disbarred from the Cambodian Lawyers Association. However, this lawyer continues to pursue, up to a point, where the government gives him a hard time.

In your previous interview, you mentioned that, “we need to try and defend human rights until the end, and if there is no end, we need to continue and create the end.” What would you say this time to the human rights lawyers in Cambodia and elsewhere?

I think the end is justice. It is respecting fundamental rights of the defendant, human rights, human dignity and justice. Even when criminal lawyers go after criminals, they have to hold on to the principles of rule of law. For us human rights lawyer, we take oath. I told a judge once, who was also a woman that “You took an oath you need and to hold on to the law”. She could not look me in the eyes; she could not! For justice, I think looking at justice in the eyes, and those who do not look back, are those who are complacent and weaponized.

Cambodia