India

India

India

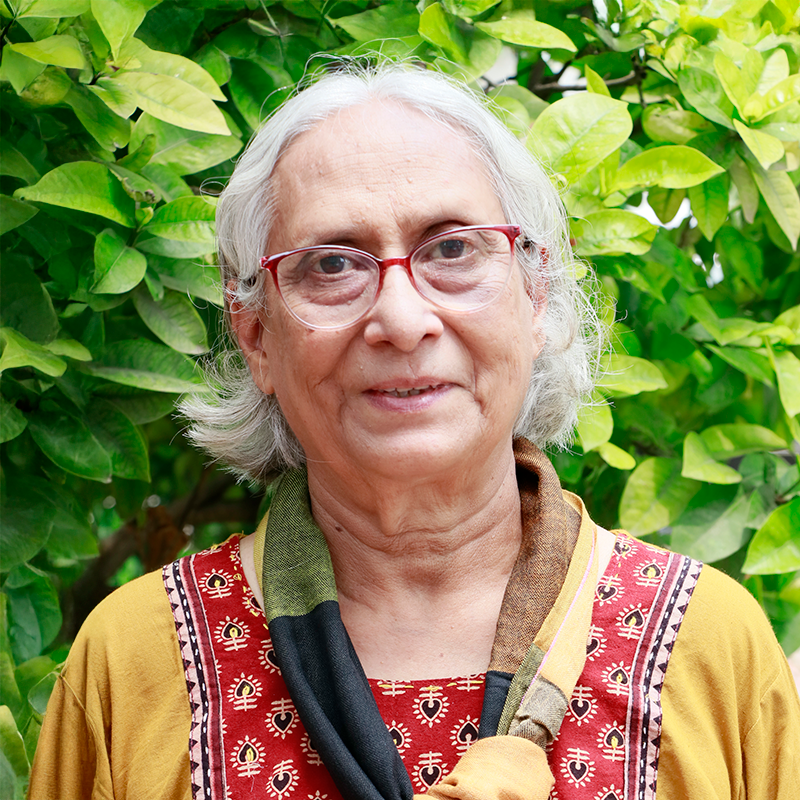

Trupti Ambrish Mehta

Trupti Ambrish Mehta

Trupti Ambrish Mehta

Activist and Coordinator at Action Research in Community Health and Development (ARCH)

Activist and Coordinator at Action Research in Community Health and Development (ARCH)

Activist and Coordinator at Action Research in Community Health and Development (ARCH)

India

Trupti Ambrish Mehta

Activist and Coordinator at Action Research in Community Health and Development (ARCH)

“The space for civil society work in India is shrinking. Governments often view organizations like ours as obstacles to development rather than as partners.”

VITA

Trupti Ambrish Mehta is an activist and serves as a Trustee and Coordinator at Action Research in Community Health and Development (ARCH), based in Vadodara, India. She holds a Bachelor of Laws and an MPhil in Linguistics. She began her professional life as an English lecturer but shifted to activism in the early 1980s. Her early work focused on the rehabilitation of tribal families affected by the Sardar Sarovar project, contributing to the development of one of India’s most important resettlement policies. From 1988 onward, she worked closely with tribal communities in the Narmada district, fighting for their land and forest rights and providing legal assistance. Between 2002 and 2007, Trupti played a key role in the national campaign that led to the Forest Rights Act (FRA). She was involved in its drafting and advocacy until its passage. Since 2008, she and her husband, Ambrish Mehta, have concentrated on putting the FRA into practice in Gujarat's tribal areas. Their use of GPS and satellite images have helped secure over 50,000 individual land rights claims. Along with that, she supports village councils in managing their forests sustainably.

Could you tell us about ARCH Vahini and what you think makes its work stand out?

ARCH Vahini was established in the early 1980s. While one group, made up of doctors and social workers, focused on community health and education, another, which I was part of, worked with Adivasi families displaced by the Narmada Hydropower Project. We soon realized that the lack of property rights over land and natural resources was the core issue for these marginalized communities. It wasn’t just about poverty or underdevelopment. It was a deeper human rights issue. These families were labeled as “illegal encroachers” whenever they farmed or used forest resources to survive. That label brought harassment, eviction, and constant state pressure. What sets our work apart is that we have always worked alongside these communities as equal partners. Both men and women have played critical roles in everything we have been able to achieve. For example, during the Narmada project resettlement, we were able to secure a policy that offered at least five acres of land to all displaced families, not just those with formal land titles but also those considered “encroachers.” And we made sure it was implemented. We saw similar success with tribal families in the district of Dediapada, near Vadodara, where we first helped stop their evictions and later worked with groups across India to push for the Forest Rights Act, which was eventually passed in 2006. This was the first law in independent India to recognize the land and forest rights of marginalized communities, including the right to manage and protect forests sustainably. Importantly, the act grants land rights to both men and women, issuing joint titles in the names of both spouses, which really matters. Passing the law was just the beginning. We have since worked closely with these communities to make sure the Forest Rights Act (FRA) is properly implemented. In the villages we work with in Dediapada, over 96% of families now have legal titles to their land. All village councils have also received collective rights for forest management. We witnessed firsthand how having legal land titles has transformed lives. People are no longer treated like criminals. They are seen as farmers and respected members of society. They are investing in their land and working to protect their forests. This benefits both the communities and the environment. Right now, we are supporting village councils to develop long-term plans for forest management.

ARCH has been instrumental in both constructive development work and advocacy. How do you see the link between this and human rights, especially for marginalized populations?

From the beginning, we have seen the need to address people’s everyday needs alongside the fighting for human rights, such as land and forest rights. So, while we work on policy changes, we also address issues such as healthcare, education, and food security. Tackling these together helps sustain the broader struggle and builds patience and resilience within the communities.

Civil society organizations like yours often face invisible and visible pushback, from bureaucratic hurdles to more direct threats. Can you share some of the challenges ARCH has faced in carrying out its mission, and how you’ve responded to them?

One of the biggest challenges we face – whether in rehabilitation work or implementing the FRA – is the Forest Department’s delays and active resistance, even after the law is in place. This can be very disheartening. But we have always chosen to stay patient. We keep working, without giving in to frustration, and we never stop trying to maintain dialogue with the government. Another recurring problem is the frequent transfer of government officers. When an officer who finally understands the issue is transferred, we must often start from scratch with their replacement.

What is the role of politics in supporting the kind of work ARCH is doing?

Right now, the space for civil society work in India is shrinking. Governments often view organizations like ours as obstacles to development rather than as partners. But we believe that the way forward is to stay engaged, even if it means adjusting our approach. For example, getting involved in implementing government programs can help build trust. It is also essential for us to stay out of electoral politics. We need to be able to work with whichever government is in power. Taking sides would damage our credibility and limit our effectiveness. Our independence allows us to stay focused on the issues and the people we serve.

What kind of international support would help safeguard civil society workers and human rights defenders in India today?

As for international support, interventions from outside are often seen with suspicion. So, any engagement must be thoughtful and sensitive to the local context.

India