Russia

Russia

Russia

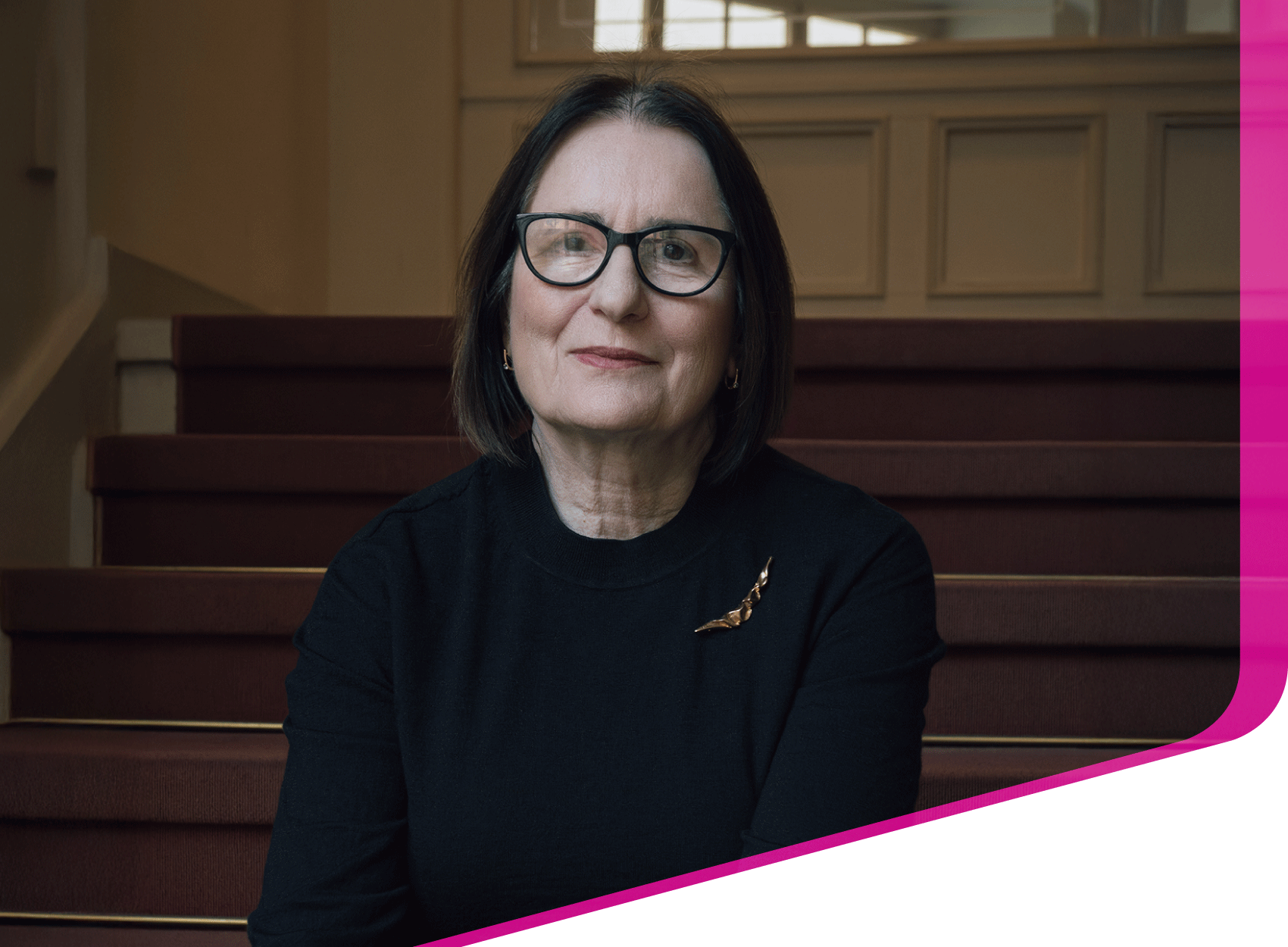

Irina Scherbakowa

Irina Scherbakowa

Irina Scherbakowa

Historian, writer, and human rights defender

Historian, writer, and human rights defender

Historian, writer, and human rights defender

Russia

Irina Scherbakowa

Historian, writer, and human rights defender

“Today, just like back then, hope comes from that same place: from memory, from speaking the truth, from dialogue. Even when everything looks dark, it is crucial to keep talking, listening, and documenting.”

VITA

Irina Scherbakowa is a historian, writer, and human rights defender. She co-founded Memorial in 1988. Born in Moscow in 1949, she graduated from Moscow State University and holds a PhD in philology. Since the late 1970s, she has collected oral histories from former GULAG prisoners, laying the groundwork for Memorial’s documentation of Soviet repression. After the collapse of the USSR, Memorial combined human rights advocacy with historical education. In 2014, the Russian state labeled it a “foreign agent,” and in 2021, the Supreme Court of Russia shut it down. Soon after, members faced criminal charges for “rehabilitating Nazism” and distorting Soviet history, showing how threatening memory work is to Putin’s regime. In 2022, Memorial received the Nobel Peace Prize alongside Belarusian activist Ales Bialiatski and Ukraine’s Center for Civil Liberties. For Memorial, this recognition affirms a core belief: confronting Stalinist repression, state violence, and historical lies is essential. Without addressing crimes of both the Soviet and Putin regimes, there can be no basis for justice, democracy, or trust. Honest reflection on history helps prevent future violence and authoritarianism. Until 2022, Irina led Memorial’s educational work in Russia. Now in exile, she continues this mission in Germany and co-founded Memorial Zukunft. She publicly denounces Putin’s regime and the war in Ukraine.

What made you start collecting interviews with former GULAG prisoners?

Usually, the next generation wants to learn about their parents’ childhood. For me, that childhood overlapped with one of the darkest chapters in Russian history – the 1930s and the years of mass terror. I grew up surrounded by people who had lived through it. Many others did not survive. My own family made it through by some strange stroke of luck. My grandfather worked for the Communist International (Comintern), and almost all his colleagues were killed. But he survived. I grew up with this story, not fully understanding at first why everyone kept saying, “We were so lucky.” At some point, I realized how important it was to speak about it. People would tell me things they had never said aloud before. For them, it was a relief. And for me, it was a realization that these were not just personal stories, but something much bigger. It was a history that never made it into the official textbooks.

What defines Putin’s regime today?

The core of Putin’s postmodern ideology is rooted in a glorified version of the past. It’s an eclectic form of traditionalism: a mix of vague philosophical references, Eurasianism, and fascist-like ideas. At first, this ideological hybridity could be confusing, but over time it has hardened into militant ultraconservatism with clear fascist features. The aggression against Ukraine, more than any other war, was justified through these historical narratives, framed as a restoration of so-called “historical justice.” What makes today’s Russian state even more frightening than the Soviet Union is its open embrace of violence. For all its brutality, the Soviet regime tried to hide torture, executions, and camps. It cloaked its crimes in lies. Today’s regime does the opposite. Violence is on display. They want us to be afraid. Torture has become normalized. Repression is the rule. People know that police torture happens and that it could happen to anyone. Believe me, there is no more effective way to instill fear in a population.

What does the war against Ukraine mean to you?

It’s a catastrophe for Russia and Russian society. And it’s a horrific, unimaginable crime against Ukraine. I realized that if I were to be of any use, it would no longer be inside Russia. Here in exile, I can speak out and be heard. Putin has failed to conquer and subjugate Ukraine. And that gives all of us hope. Our colleagues at Memorial are working closely with Ukrainian partners to document Russian war crimes in Ukraine. It’s a challenging professional work. We already have experience from Chechnya and know how hard it is to prove individual responsibility for such crimes. We support these efforts as best we can. This work matters not only for Ukraine, but also for Russia’s future when the country will need to look in the mirror with honesty.

What is your work today?

When people ask what I do, I say: I’m a lobbyist (for human rights). I explain to politicians, journalists, and the public what the Putin regime is. I often speak in eastern Germany, especially in areas with troubling election results. I see it as my responsibility to help people understand what could happen. I urge them to remember their real history instead of a nostalgic version, and I warn about the dangers of Putin’s regime and the illusions of an easy and quick peace in Ukraine. We’ve long worked with German foundations, historians, and museums. I believe that we still offer hope by showing that another Russia exists. This matters not only to us, but also to German society. When I speak about Putin’s regime or the horrors of war, my words may resonate more with German audiences, especially those I can speak to directly. Despite limited resources, we continue contributing as experts through exhibitions, lectures, and cultural work, particularly in eastern Germany. This is no coincidence: we are connected by a shared totalitarian past and the hard lessons of the 20th century. Germany is a place where Memorial’s mission can live on.

Does Russian immigration today matter politically, and what is its future?

There’s a lot of talk about how those who left no longer play a role. That’s simply not true. Willy Brandt, for example, wasn’t in Germany during the war. He came back only after 1945, yet he still went on to shape German politics. In that sense, our task might even be simpler: continuing with what Memorial has always done – preserving memory, documenting crimes, supporting human rights defenders, and speaking to society. Immigration isn’t the end; it’s a way to continue. It has become even more relevant. Why? Because in Russia, the space for open resistance is shrinking rapidly. Fewer public standards remain, and fewer opportunities to speak freely. Even so, our colleagues and friends who have stayed in Russia continue to do what they can: they write, respond honestly to questions, and pursue research as much as is still possible.

What helps you hold on to hope today?

You know, everything felt hopeless in the late 1970s. The dissident movement had been crushed, people were in prison camps, and the war in Afghanistan had begun. It seemed like the system, even though it was post-Stalinist, was still rigid and impenetrable, and that nothing would ever change. Even the prospect of Brezhnev’s death didn’t inspire hope. At that time, I went through a serious personal crisis. And it was precisely then that my work on interviews, speaking with former prisoners, and hearing their memories saved me. It gave me a sense of meaning and direction. Today, just like back then, hope comes from that same place: from memory, from speaking the truth, from dialogue. Even when everything looks dark, it is crucial to keep talking, listening, and documenting. That’s what keeps us from falling into despair.

Russia