Turkey

Turkey

Turkey

Barış Altıntaş

Barış Altıntaş

Barış Altıntaş

Journalist and human rights defender

Journalist and human rights defender

Journalist and human rights defender

Turkey

Barış Altıntaş

Journalist and human rights defender

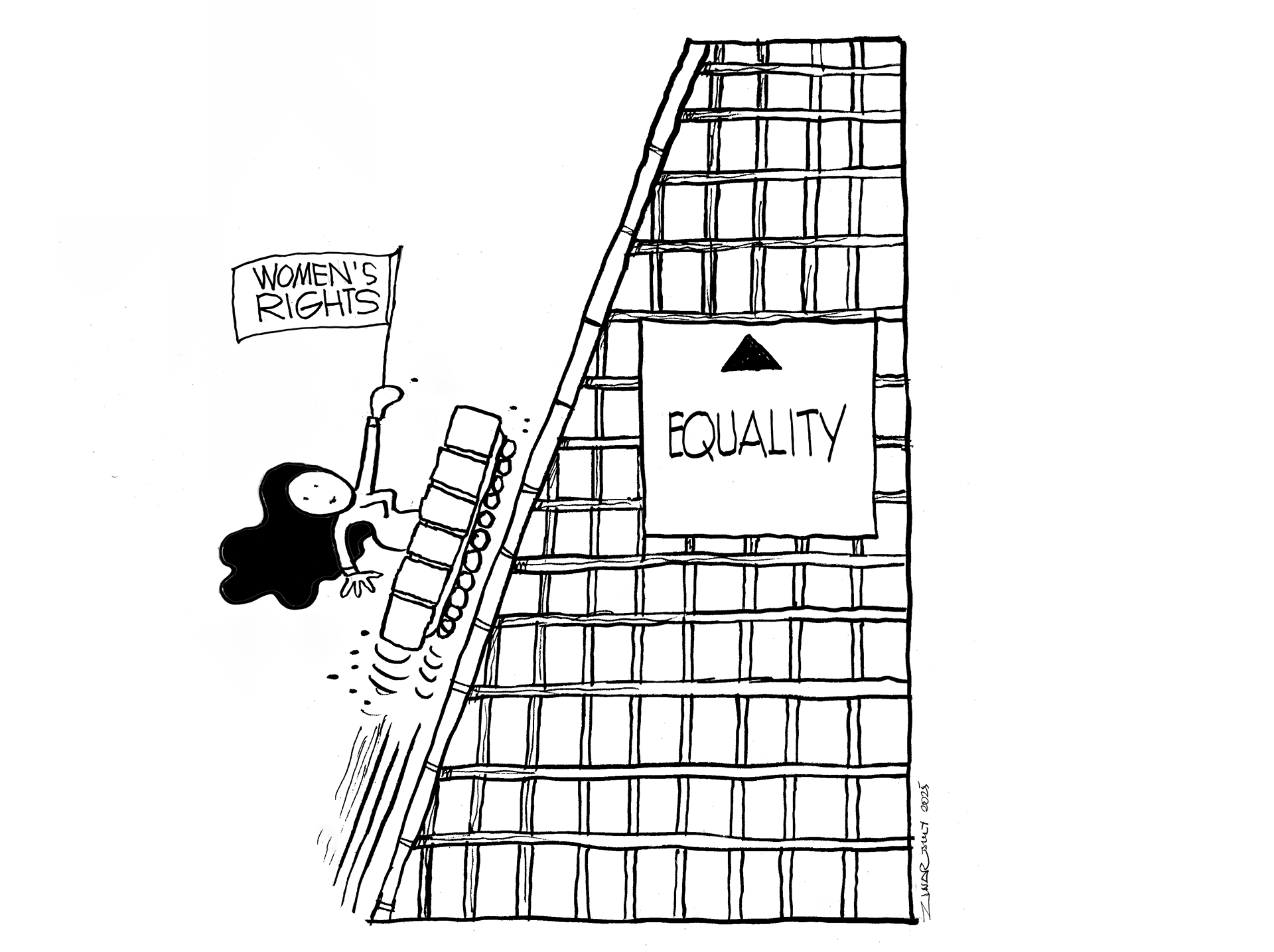

“The message to civil society actors is: don’t give up!”

VITA

Barış Altıntaş is an Istanbul-based journalist and human rights defender. She began her career reporting on politics, women’s rights, and science for outlets such as the Economic News Agency (EBA) and the Turkish Daily News in Ankara and Istanbul. Over the years, she contributed as a freelance journalist to international platforms including Tageszeitung and Index on Censorship, focusing on press freedom and democratic backsliding in Turkey. From 2016 to 2018, she worked as a justice reporter, covering political trials and documenting violations of fair trial standards. Barış is a co-founder and currently co-director of the Media and Law Studies Association (MLSA). This non-profit organization provides legal defense for journalists and activists, runs one of Turkey’s most extensive freedom of expression trial monitoring programs, and offers training and professional development for human rights lawyers and media workers. She is also a founding board member of the Balkan Network of Science Journalists (BNSJ). Committed to building bridges between media and legal communities, Barış advocates for principled solidarity and accountability in an increasingly repressive environment.

What was the turning point in your professional career that motivated you to work at the intersection of media, law, and human rights?

I would say it was the realization that there is a “divide-and-conquer” mentality that makes it possible to continue to apply authoritarian crackdown and pressure. I worked as a journalist until 2015, then I went into civil society, engaging with freedom of expression and journalism. Shortly after the coup attempt, it hit me strongly how incredibly important the work of civil society was, something that I hadn’t maybe realized to that extent before. With the coup attempt and an ever-stricter administration in Turkey, the need became more apparent. It also showed me our deficiencies as a society, particularly concerning the journalists' community. In other words, it wasn’t just the state pressure after the 2016 coup attempt that pushed me into this field – it was also a deep frustration over the fragmentation within the media community itself. I was disheartened to see how journalists often failed to stand together across ideological lines, even as their colleagues were arrested or silenced. The inability to stand up for each other, no matter how you disliked each other's politics or outlook, was very frustrating. There was no shared defense of fundamental values like freedom of expression and democratic accountability. That realization – the lack of unity around basic principles – drove me to co-found MLSA. We wanted to build an organization that would remain neutral and principled, offering support to any journalist or activist whose case falls under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, regardless of their views or affiliations.

How does the Media and Law Studies Association support human rights defenders in Turkey, and what impact does this have on civic resilience?

MLSA works on several fronts. We provide free legal support to journalists, academics, artists, and activists facing legal harassment for expressing their views. Our extensive trial monitoring program documents freedom of expression cases across Turkey. We also offer capacity-building for human rights lawyers and provide professional development opportunities for journalists. Through advocacy – both domestic and international – we amplify the voices of those under pressure and help to ensure they are not left isolated. This web of support enables human rights defenders to keep going, which is essential for civic resilience in an increasingly repressive environment. Another area we work in is online freedoms and digital civic space. We are also increasingly supporting Civil Society Organizations in their capacity-building efforts. This is a new area in which we are looking to focus more on protecting smaller organizations against problems during state audits, which are increasingly targeting LGBTQI+ and other vulnerable organizations with malicious intent, I must say.

Your work often involves documenting rights violations and ensuring fair trial standards. How does this contribute to holding governments accountable, and what systemic challenges do you encounter in this process?

Documenting trials and rights violations has a great impact in the long-term and short-term. Supported by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation from the get-go and continuously to varying extents, our monitoring produces reports and data feed into international accountability mechanisms – especially Rule 9.2 submissions to the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers, which tracks the implementation of European Court of Human Rights judgments. Solid, quantitative data is critical in that context. Locally, our data is also used by NGOs for advocacy and research. Beyond documentation, simply being present at hearings matters – it shows solidarity for defendants, and for the judiciary, it’s a reminder that decisions are being observed. We also try to bring international observers to courtrooms, to further amplify visibility and pressure. This combination of presence, documentation, and advocacy is our way of pushing back against systemic injustice.

Have you personally faced any threats?

Although I haven’t received any direct threats, I have occasionally been targeted by online trolls because of the work we do. More broadly, it is deeply stressful to operate in a legal environment where rules can be applied arbitrarily. The unpredictability of the system, especially when it comes to freedom of expression cases, creates a climate of constant uncertainty. That in itself is a form of pressure – one that makes the work both urgent and emotionally taxing.

Looking ahead, what are your expectations from the international community, and what is your message to other civil society actors in Turkey and around the world?

We ask the international community for sustained, principled engagement – not just during moments of crisis, but as a long-term commitment to the values we all claim to uphold. This means providing political support, yes, but also funding structures that are accessible and flexible enough to meet the needs of frontline organizations. The message to civil society actors is: Don’t give up!

Turkey