PAKISTAN

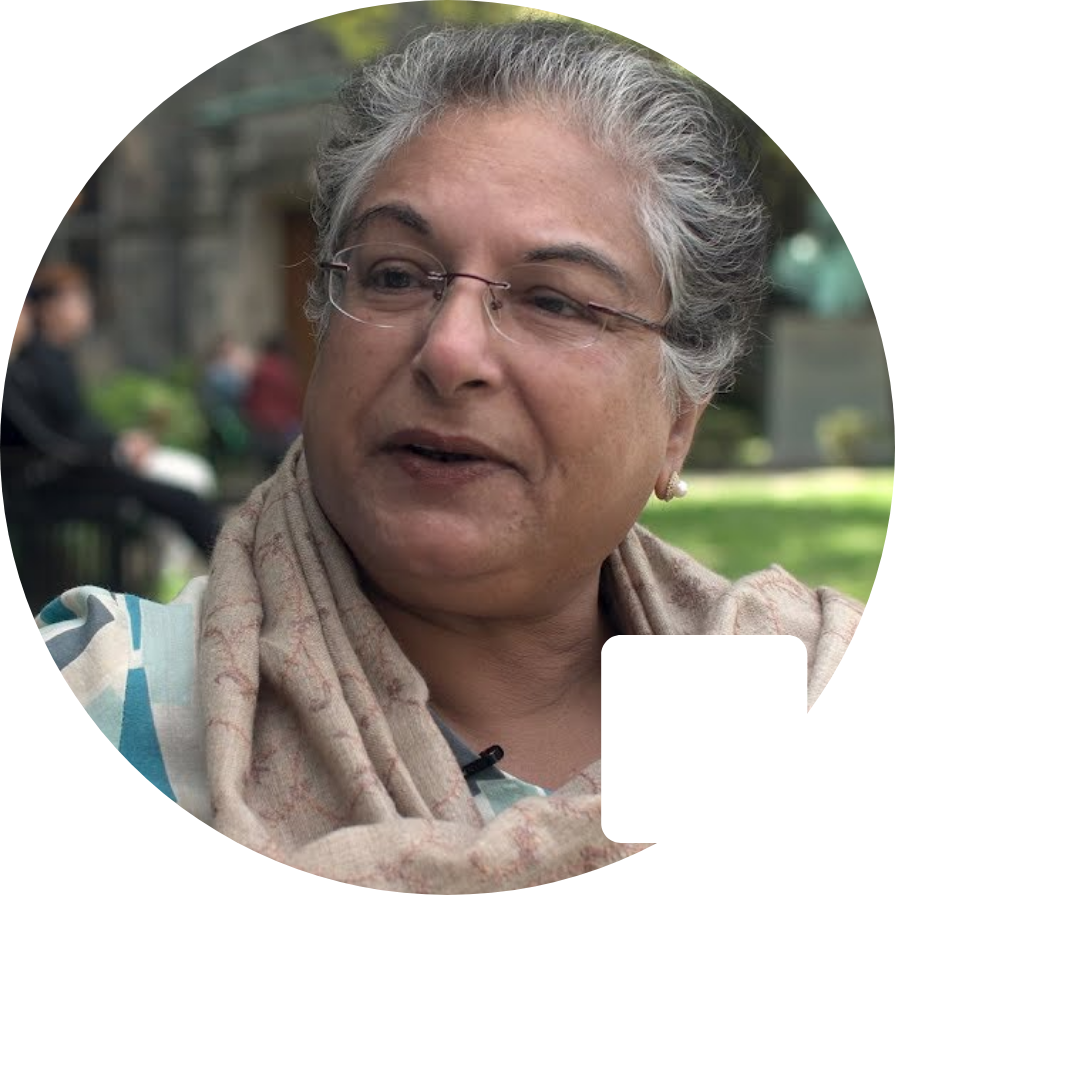

Hina Jilani

One of the founders of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) and its current chairperson, Hina Jilani is a leading human rights defender at national and international levels. She has been at the heart of Pakistan’s women movements, championing women’s rights fearlessly despite hostile threats and propaganda. In 1980, she founded Pakistan’s first all-women law firm, and the Women’s Action Forum. She is also one of the founders of Dastak, a shelter that provides legal aid and refuge to the survivors of gender-based violence. In 2000, Hina Jilani became the first Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Human Rights Defenders, through which she worked to empower and protect rights defenders worldwide. She also served as a Member of the International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur in 2004; Member of the Eminent Jurists Panel on Human Rights and Counter Terrorism in 2006; and Member of the United Nations Fact Finding Mission on Gaza in 2009. In 2013, Hina Jilani was elected to join the International Commission of Jurists; and in 2020, she was appointed to an International Commission of Inquiry into Systemic Racist Police Violence Against People of African Descent in the United States. A pioneer of human rights, she has also received numerous awards and honours, such as the 2001 Millennium Peace Prize for Women and the 2020 Stockholm Human Rights Award.

VITA

One of the founders of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) and its current chairperson, Hina Jilani is a leading human rights defender at national and international levels. She has been at the heart of Pakistan’s women movements, championing women’s rights fearlessly despite hostile threats and propaganda. In 1980, she founded Pakistan’s first all-women law firm, and the Women’s Action Forum. She is also one of the founders of Dastak, a shelter that provides legal aid and refuge to the survivors of gender-based violence. In 2000, Hina Jilani became the first Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Human Rights Defenders, through which she worked to empower and protect rights defenders worldwide. She also served as a Member of the International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur in 2004; Member of the Eminent Jurists Panel on Human Rights and Counter Terrorism in 2006; and Member of the United Nations Fact Finding Mission on Gaza in 2009. In 2013, Hina Jilani was elected to join the International Commission of Jurists; and in 2020, she was appointed to an International Commission of Inquiry into Systemic Racist Police Violence Against People of African Descent in the United States. A pioneer of human rights, she has also received numerous awards and honours, such as the 2001 Millennium Peace Prize for Women and the 2020 Stockholm Human Rights Award.

Why did you decide to become a lawyer and focus on human rights?

The legal field appealed to me, because my father was a human rights activist and a politician. His various imprisonments as a political leader made me familiar with the constitutional framework and the court environment in Pakistan. That is the inspiration, which motivated me to join the legal profession. I was the first in my family who became a lawyer.

What was your experience when you started practicing law as a woman in Pakistan?

At the very beginning of my legal career, I was one of the very few women lawyers in the country and probably even one of the first fewer women who practiced law in the courts. It was a difficult environment seen from outside, but once you were in it, it was welcoming. My male colleagues did not take me seriously. Once I entered the profession, my commitment to stay there became stronger than before.

What were the challenges you faced during your career taking up human rights cases?

The challenges started very early on in my career, when I realized that practicing law is a privilege, which I had to use it to support the underprivileged, who needed access to justice, but could get it due to financial or social reasons or because they were politically marginalized. Taking up human rights causes in a country, which is amenable to repressive governance, is very difficult. Another big challenge was the social prejudices against the vulnerable groups in Pakistan, particularly women, non-Muslim minorities and bonded labour, seeped into the judicial mindset and tamper with the impartiality of the judiciary. I handled these cases at the start of my career in the 1980s during the time of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, who with a very repressive military regime used Islam as a weapon, especially against women and non-Muslim minorities. I was not only a legal practitioner dealing with cases of discrimination against women and non-Muslim minorities, but also a human rights activist and defender, who was out on the streets and raised her voice against the repression.

This kind of profile invites a backlash and it did. It came from both the state and non-state actors. I suffered imprisonment, house arrest and beatings on the street by the law enforcement agencies. I received death threats. One of the extremist groups raided my house, and my family members were taken hostage. Private actors targeted me after I started a shelter for women. Moreover, family members of those victims, who were in danger of honour killings, became very hostile towards the shelter and me. I remember one particular case of honour killing, when a girl’s family killed her, while she was standing in my office right next to me. I have had these experiences, but this has not changed my commitment to my work. If I see injustice, I cannot turn my face away. I cannot complain about injustice in our state or our society, if I do not stand up and do something against it.

What is the cause you feel most strongly about?

One of the most painful processes that I went through it was fighting for women’s rights in this country, especially their social rights, such as their freedom of choice in marriage, their right to life and individual liberty. Although it was painful, I believe, this is where I got the best results. When I started my law practice, the environment for women’s rights was very difficult. The prejudices of the judiciary against women were just as strong as the social bias. Nonetheless, I am happy to say that we have made a very big contribution to changing this mindset and the law. Over the years, we have managed to give women’s rights a place in our legal framework.

How do you see the role of the legal profession in upholding the rule of law in Pakistan?

The legal fraternity in Pakistan has a long history of standing on the side of the rule of law. We have big names of lawyers taking pro bono cases of those who promote democracy, human rights or the rule of law, fighting for a cause than just a case. However, there are differences in the Bar and there are times when it gets politically divided. We cannot categorically say that lawyers protect the rule of law just because they deal with the law. I see the tradition of the Bar upholding the rule of law, but it is somewhat weakened nowadays. Nevertheless, we still respect the views coming from the Bar. The courts are important institutions and we, the lawyers, need to ensure that the courts are always respected. The courts themselves shall also realize that they have to stand up for their constitutional responsibilities, and most importantly protect people’s rights and make sure that access to justice is provided. This is the reason why I still appear before the courts in spite of all the frustrations I have had during the 40 years of my law practice. We have to ensure that the courts are not sidelined.

“I cannot complain about injustice in our state or our society, if I do not stand up and do something against it.”

How do you see your human rights engagement developing in the future?

I do not see my human rights engagement waning. The situation in Pakistan has always been as such that it does not allow us to sit back and watch. We need to stand up and do something about it. I am still as committed as I was at the beginning of my career.

Do you have any messages to the human rights lawyers?

I can say from my experience that there are always difficult times, but we have to make sure that we believe in our struggle for the promotion of the rule of law and human rights. Our hope is in our struggle. If I keep this struggle going, there will be success in the end. Even a small success gives me more energy for the next time, because there will always be a next time. There will never be a time that I would say it is enough and I will stop doing this.

Pakistan