Egypt-Tunisia

Egypt-Tunisia

Egypt-Tunisia

The Déjà-vu

The Déjà-vu

The Déjà-vu

By Mohammed Mostafa

By Mohammed Mostafa

By Mohammed Mostafa

Egypt-Tunisia

The Déjà-vu

By Mohammed Mostafa

“Tunisia was the last hope for democracy in this region.”

VITA

Mohammed Mostafa is an Egyptian human rights and democracy activist, and a researcher in the field of freedom of expression, students' rights, and academic freedom. Mostafa has extensive experience working with civil society organizations like the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, and the Law and Society Unit at the American University of Cairo, where he designed programs on economic, social, and cultural rights and monitored human rights developments. Currently, he is the Executive Director of the Intersection Association for Rights and Freedoms. Mostafa has authored numerous reports, policy briefs, and opinion articles. He has also coordinated campaigns and workshops related to student rights and freedoms. In Tunisia, while in exile, he edited many reports on institutional human rights violations on freedom of expression, and the right to peaceful assembly.

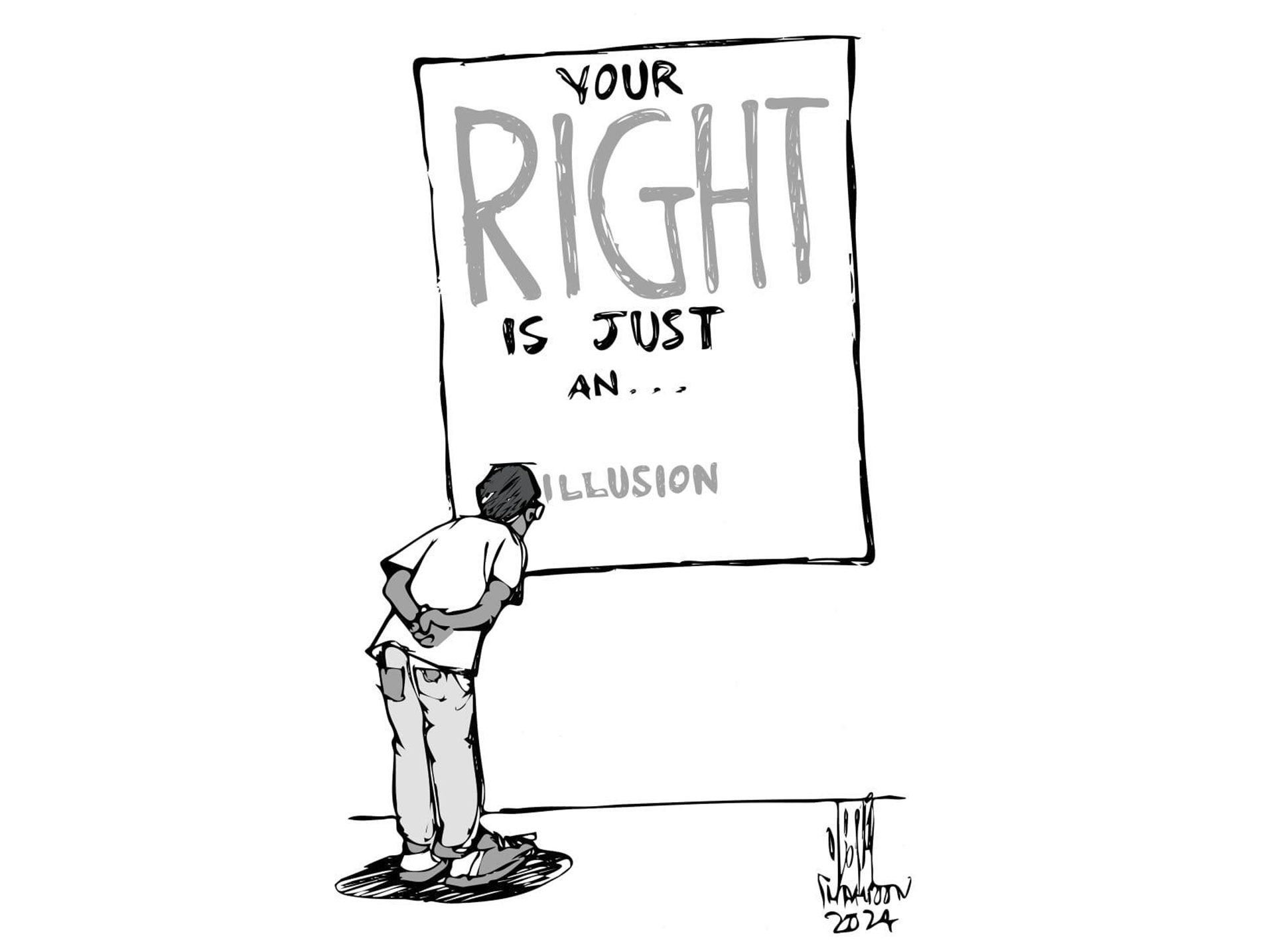

We all know the déjà vu phenomenon, the meaning of déjà vu (in English: Deja Vu) is "seen before". It is a French word, where a person feels a repetition of a situation or scene, although it has not happened before, or they may feel that they have already seen an event or place they are visiting for the first time or a person they have never seen before.

I was 22 years old when the military coup took place in Egypt in July 2013. I witnessed all the human rights violations committed by the regime in Egypt when I was a student activist and then became a researcher at an Egyptian organization called the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF). My work there focused on monitoring and documenting violations of freedom of expression, student rights and freedoms, and academic freedom. Along with my colleagues, I witnessed many violations that targeted human rights defenders in Egypt. I experienced the arrest of the head of the organization's board of trustees, its executive director, his wife, and three other colleagues, as well as the enforced disappearance for six months of my colleague Ibrahim Ezz El-Din.

It is not easy at all, psychologically and practically, to witness your colleagues and friends at work, who are supposed to be defending human rights, being subjected to these violations.

It is not easy at all, psychologically and practically, to witness your colleagues and friends at work, who are supposed to be defending human rights, being subjected to these violations.

It is not easy at all for your colleagues to also become victims of violations, and for you to document their cases and write about them. Egypt became an extremely hostile environment for human rights work. The authorities completely closed the public sphere, and everyone faces the danger of arrest and enforced disappearance.

I faced potential security risks, and as a result, I moved to Tunisia under an international program for the protection of human rights defenders at risk. I arrived in Tunisia in July 2019. At that particular time, Tunisia was a center for many international human rights NGOs and human rights defenders. It was also the only country under democratic rule amid the failure of the Arab Spring revolutions. It was not a country that fully embraced rights and freedoms, but it was far better than its neighbors in the MENA region. During this period in Tunisia, I witnessed many violations, especially regarding the right to peaceful assembly, where the police cracked down on many protests and protesters were killed. I documented this and conducted interviews with victims of these violations through my work at the Intersection Association for Rights and Freedoms. The culture of fear was not prevalent among activists and human rights defenders, despite these violations.

On the evening of 25 July 2021, on Tunisia's Republic Day, which marks Tunisia’s transition from a monarchy to a republic, President Kais Saied decided to suspend the elected Tunisian parliament, suspend parts of the constitution, and monopolize all powers in his hands.

Tunisian crowds took to the streets to celebrate the removal of Islamists from power. Here, I felt a déjà-vu.

After Sisi removed Mohamed Morsi from power, millions in Egypt took to the streets to celebrate. Fear took hold largely, and I saw my friends and colleagues happy with this victory. But it is impossible for the premises, actions, and behaviors to be similar and for us to expect different results!

Over nearly three years since Kais Saied's seizure of power, he has amended the Tunisian constitution alone without any participation from active political forces, held parliamentary elections that did not have the same popular participation as before, and issued numerous laws and decrees that have been used to violate the right to freedom of opinion and expression and freedom of journalistic work, such as his Decree No. 54 of 2022. Under this decree, more than 30 activists, politicians, and journalists are currently being prosecuted for criticizing the ruling authority. In February 2023, the ruling regime launched a widespread campaign of arrests against opponents from various political forces, accusing them of conspiring against the security of the state. The same thing happened in Egypt, but at a faster pace and with much greater brutality. In the same month, President Kais Saied unleashed a widespread racist campaign against migrants from sub-Saharan, which led the police forces to launch a systematic campaign to forcibly deport them, resulting in cases of torture and death for some of them.

It is no longer hidden from people that President Kais Saied intends to monopolize power and bring dictatorship back to the country after the period of democracy that prevailed.

Now, all human rights defenders in Tunisia face the risk of arrest due to their human rights activities. There is no longer freedom of opinion and expression in Tunisia, and any criticism of the ruling authority, whether on social media platforms, television programs, or radio, is immediately punished under Decree 54. Some politicians and media figures are now in prison because of this. In addition, starting in May 2024, the regime arrested the head of a human rights organization and a former head of another organization and summoned many civil society workers for investigation due to their activities in support of migrants from Sub-Saharan countries to Tunisia.

Now, I feel that I have lived through this twice with the same events, once in Egypt and now in Tunisia. The saddest thing is that Tunisia was the last hope for democracy in this region, and it is now fading. I feel afraid for my friends and colleagues in Egypt, and now I have the same feeling for my colleagues in Tunisia and myself, as Tunisia is no longer a safe country for human rights defenders.

Egypt-Tunisia